The 37.8 fallacy

So there's a graph that pisses me the hell off.

I was going to start by talking about how I picked up the book Atomic Habits by James Clear.1 I'd build up ethos by talking about my overwhelmingly-negative experience with self-help / pop psychology as a genre, drop a one-liner here or there, and have my audience salivating.2 The first problem with doing so is that it'd be hard to convince anyone that I'm nevertheless opening this book with humility and an open mind— but I am, and I don't want to come off as though I'm doing an MST3K of Clear's book.

The second is that, for the most part, what I'm about to describe is a separate ball game from the usual reasons I find pop-psych-life-advice grating. Some of the usual problems pop up. Despite mentioning that he's written for Forbes and the like, Clear comes off as "just a guy". As far as I can tell, he's never made his ideas bare their necks for reviewer #2. He also habitually makes anecdata-forward claims about the psychology of most-to-all humans (leaving me, a woman unlike most-to-all humans, wondering whether this is relevant). But he's not a professional contrarian, nor did he outright fabricate data. He's not asserting typologies out of nowhere, nor does he claim that the mental world entirely determines the physical. And whatever problems I have with this book, it isn't lobster facts for begrudgingly-repsectable slur collectors, nor is it bait for aspiring owners of a local chain of pizzerias3.

No, this isn't about Atomic Habits as a whole. This is about the goddamn graph.

The graph

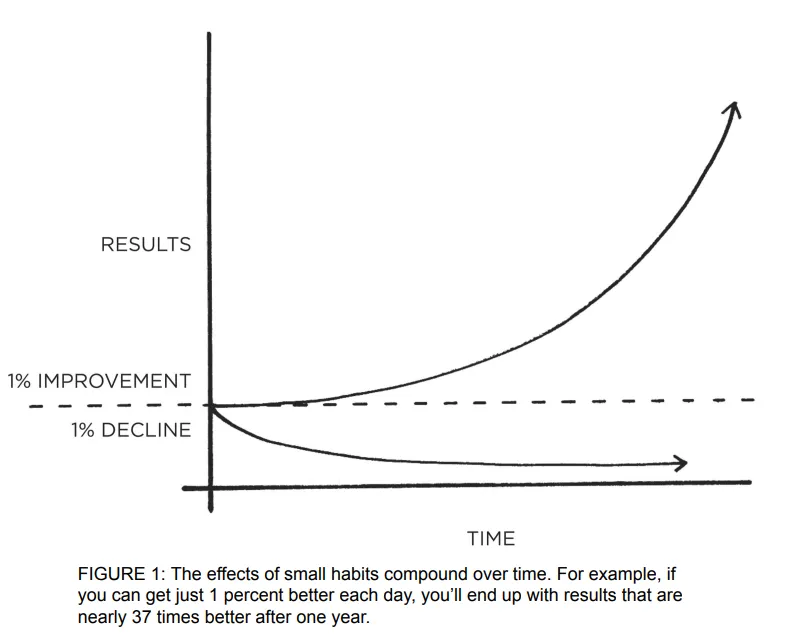

Here's the graph, from page 16 of my copy of Atomic Habits (Cornerstone Press, 2022):

Here's how Clear describes the increasing curve on that graph in prose:

Meanwhile, improving by 1 percent isn't particularly notable— sometimes it isn't even noticeable— but it can be far more meaningful [than one defining moment], especially in the long run... Here's how the math works out: if you can get 1 percent better each day for one year, you'll end up thirty-seven times better by the time you're done. (15)

Finally, here's that graph as an equation:

The first thing I notice about this graph, which is admittedly nitpicky, is that its caption states that 37.8 is "nearly 37". That's denotatively true but the first time I've ever seen "nearly" as truncation, rather than rounding up. Funnily enough, this supports Clear's point: whether 37 or 38, the result of the equation is unexpectedly large given the premise of "doing 1% better for 365 days". The point is that, after just one year with Clear's paradigm, we will look back toward where we started and see a rounding error.

Indeed, the thing this graph is asserting is that habits "compound" in a way best described by exponentiation. In this chapter Clear loves comparing habits to instances of exponential growth:

Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement. (16)

Breakthrough moments are often the result of many previous actions, which build up the potential required to unleash a major change... Cancer spends 80 percent of its life undetectable, then takes over the body in months. (20)

If habits are like exponential growth, there are two clear conclusions. The first, of course, is that his secrets hold the potential for massive change. (Minimum wage times 37.8 is a million-dollar salary!) The second is that there is what Clear calls a plateau of latent potential, the feeling of discontent or frustration that forms due to exponential growth having a slow start.4 If you got 1 cent today, 2 tomorrow, 4 the day after, and so on, you'd end up with Balatro-sized numbers after a month— but for the first week, you'd be in the plateau, jealous of the chumps who had millions now, wondering if your money really would add up.

This has a clear implication for Clear's audience: good habits won't give results right away. This isn't a get-rich-quick scheme, it's an argument specifically for doing the work right now, even if it seems inconsequential, and even if it seems like doing so won't put you on track to your goal. As the book's tagline says: "Tiny changes, remarkable results". Trust in the exponent.

An interlude: making math make sense

This is as good a time as any to explain some math terms in plain English, really fast and loose.5

When someone says exponential growth, our first thought is "oh god": pandemics, population collapse, infinite money glitches. Not only does an exponential function keep growing, the rate at which it keeps growing keeps growing, and the rate at which that growth is growing keeps growing, and the rate of that growth's growth's growth keeps growing, and so on forever and ever. What this means is that, no matter how slow they start, they eventually shoot up faster than we're equipped to perceive. Again: pandemics6, population growth, infinite money glitches.

Exponentials are some of the many, many functions that "curve up" when you draw them on a graph (as opposed to being a straight line or curving down). These functions that curve up are called convex. All convex functions, exponential or not, grow faster and faster, which is called accelerating. (The opposite of accelerating is diminishing returns.)

By contrast, linear growth, well, looks like a line when you draw it. While the growth rate of a convex function depends on where you are, a linear one has a constant growth rate. (That's why, in visual terms, every cross-section of a line looks the same.) What this means in real life is that the a linear increase is not accelerating, and it's not giving diminishing returns.

To summarize:

- If the amount of money you have is a linear function of the number of apples you sell, you're selling them at a constant price. You're not making money faster and faster, but you are steadily accumulating money.

- If the amount of money you have is a convex function of the number of apples you sell, each apple makes more money than the last. Your profits aren't just growing, they're accelerating— your salary is growing, not just your savings account.

- If the amount of money you have is an exponential function of the number of apples you sell, you will probably go from "quite rich" to "worth more than all the diamonds in the solar system" in the blink of an eye.

The flip side

I wanted to establish these ideas because some of Clear's metaphors aren't exponential at all.

Imagine that you have an ice cube sitting on the table in front of you. The room is cold and you can see your breath. It is currently twenty-five degrees. Ever so slowly, the room begins to heat up.

Twenty-six degrees.

Twenty-seven.

Twenty-eight.

The ice cube is still sitting on the table in front of you.

...

Thirty-one.

Still, nothing has happened.

Then, thirty-two degrees. The ice begins to melt. A one-degree shift, seemingly no different from the temperature increases before it, has unlocked a huge change. (20)

I have asked every science teacher I've ever had why we experience discrete states of matter despite experiencing continuous temperature. I'm convinced there must be a function out there with exactly two roots representing melting/freezing and boiling/condensing, and nobody I've talked to seems to know what it is. I haven't found it, so I can't say for sure that the melting process is not exponential on some deep level. But broadly, this is just a rapid and discrete change— a perceptual experience we associate with exponential functions, but not really exponential.

The impact created by a change in your habits is similar to the effect of shifting the route of an airplane by just a few degrees... If a pilot leaving from LAX adjusts the heading just 3.5 degrees south, you will land in Washington, D.C. instead of New York. (17)

This isn't exponential either. The gap in our intuition that causes the unexpected result isn't the power of compounding interest. It's trigonometry, U.S. geography, and the fact that 3.5 degrees is a pretty sizable angle, all things considered. The relevant function is barely convex. If this is a fitting metaphor, it has huge implications for Clear's thesis. Whatever is happening here, it doesn't really compound, and therefore it neither rewards consistency nor causes a plateau of latent potential.

Time magnifies the margin between success and failure. It will multiply whatever you feed it. (18)

Obviously this isn't meant to be a precise mathematical description of the relationship between habits and time. We might interpret this "multiply" as exponentiation, as in "go forth and multiply". However, the idea of "multiplying by time" brings to mind linear examples: distance being a constant rate multiplied by time, or payment being a constant hourly rate multiplied by time. It seems to me that Clear is now saying that "compounding" just means "aggregation", not "accelerating". In other words, he's implying this still-impressive equation:

Speaking of which, why is exponentiality a better metaphor than linearity, anyway? Why would habits be unlike goods that, when sold consistently at a constant price, make you rich over time without the plateau Clear describes? His evidence for the exponential compounding effect takes the form of athletes who stack up hundreds of habits— but no matter what the status of habits, we'd expect an athlete with better beneficial habits to outperform an athlete with worse ones. The only requirement for that to be true is that habits provide any sort of returns at all (even the lowly diminishing returns). So, let's investigate for ourselves.

The self-defeating metaphor

For a moment, let's take this exponentiation metaphor as seriously as possible. Let's imagine that I can lift a measly 10 pounds, for which I'm being crammed into lockers constantly. Not to worry! I've read Atomic Habits, and have resolved to lift a weight that's 7% heavier each week. This should be easy; after all, 7% per week is actually smaller than 1% per day, because there's less compounding. And as Clear indicates, I'll be a hulk freak soon.

Week 1: I can lift 10 pounds; this week I have to add 0.7 pounds to my barbell. I'm a shrimp with a lot of room to grow, so this is no problem. Just practicing a little every day is more than enough.

Week 2: I can lift 10.7 pounds; I have to improve this by a smidge more than 0.7 pounds. Again, my new training routine is more than enough. This is great!

Week 13: Skipping ahead. I can lift 24 pounds and change, which isn't bad— but I'm in the plateau Clear describes now. I don't think I'm on track to lift a 300-pound boulder in just nine more months. What's worse, I have to add another 1.5 pounds this week, which seems a bit intense.

Week 26: Oh, god. I'm supposed to be at 58 pounds now. I have a long way to go just to catch up with the accelerated rate at which I'm supposed to be making gains. I look with apprehension at the additional four pounds I'm supposed to add to my barbell this week.

Week 39: If I had gone from a dork who could barely lift ten pounds to a beast who can lift 140, I would be happy— but sadly, I'm not there. I'm beginning to lose hope. In a few weeks I'll be adding 10 pounds to the pile, and that just seems impossible.

Week 52: I've long since given up on the "atomic method". I'm supposed to be at 337 pounds— much less than the amount I'd need if I compounded daily, but nevertheless more than it would be reasonable for me to ask. It's a shame, too— if I had stuck with it, in just another short year I'd be able to lift a 10,000-pound elephant.

If the horse isn't beaten to a pulp already, my point is that the exponential growth Clear describes is detached from any numbers anyone has ever actually experienced. I'll say that again, because it's remarkable: the factor that makes Clear's seem worthy of a bestselling book, exponential growth, is the very thing that makes this scenario over-the-top unrealistic. The issue is that, on our scale, 1% and 0.1% as basically the same number: "very small". So, as a result, it's easy to believe that "improving by a constant 1% each day" is a reasonable goal, and not a recipe for a rice-on-chessboards situation. This is a cool hole in our intuition: we can assert that exponential growth isn't that intense, use that fact to smuggle the 37.8 equation under our radars, then turn around, realize that exponential growth is actually that intense, and be in awe!

By now you may be shouting at the screen that I'm taking a metaphor too seriously. Obviously, Clear doesn't think I could literally run a mile 37.8 times faster over a lifetime, much less a year. What he says demands interpretation. The question, though, is this: how are we supposed to interpret him? Clear says repeatedly that successive habits bring increasing utility. In other words, if his metaphor-function isn't exponential, it's at least concave. And Clear introduces this idea of compounding with the phrase "Here's how the math works out" (15), implying that this is evidence rather than metaphor or a claim that needs evidence. Many speakers would hedge this sort of fantastic claim, say "now obviously that's an exaggeration, but..." in some later paragraph. But Clear says nothing of the sort.

The book doesn't takes the "37.8 equation" literally, but it does take it seriously, believes that it's at least spiritually true. I imagine Clear as believing in a sort of Dragon Ball Z-style spiritual power level that does actually scale exponentially, which manifests in some dampened way in the realm of the corporeal. The meat of the book, however, is based on much weaker claims— much of what Clear says about "compounding" is true if our metaphor-function is merely concave, or even linear. Much of what he says about "increasing" is even true if our function gives diminishing returns!

The result is largely phatic. It sits somewhere vulnerable on the incline between motte and bailey. "Whatever I'm saying about habits," the book taunts, "you need to listen close."

Vivisection

The obvious question is why; the obvious answer is genre convention. James Clear tells us that habits are exponential for the same reason that Airheads shows us a child's head exploding upon ingestion. Savvy consumers in the world of books that promise "life-changing tools" expect hyperbole. A genre-aware reader will preemptively treat statements with a grain of salt, which necessitates more hyperbole, which reinforces a stable equilibrium. The book seems convinced that its readers are skeptical of the uncontroversial idea that habits are important, and assumes they will remain skeptical until numbers and graphs get involved.

There's also the fact that the psychological state-time Clear describes— times of doubt, preceding a glorious reveal that those who followed the teachings steadfastly will be rewarded— is also self-reinforcing. This eschatological factor is an emergent property of a long period of less-than-linear growth followed by a drastic rise, two traits of exponential functions that Clear outright states that his model of habits has.

I'm personally most intrigued by a third explanation, though: that the metaphor of exponentiation has become muddled. How many times have I heard the word "exponential" used to mean "accelerating" or "convex"? Hell, how many times have I heard the word "exponential" used to mean specifically "quadratic"? For many rhetors, the following are equivalent to "exponential"7:

big

increasing

convex / accelerating / growing faster and faster

strongly convex (i.e. accelerating at least as "fast" as a quadratic)

soon to be a problem

inevitable

about to change faster than we can process

synergistic / compounding

If you'd like a concrete example of this being an issue: "Activists say that climate change is exponential (about to change faster than we can process) but measurements show that it's not exponential (the rate of temperature increase isn't compounding)."

Indeed, the exponential-linear binary is the most pervasive since gender. And we've only discussed the exponential side! "Linear", which has meanings other than "growth proportional to the input"8 (such as "sequential" or "syllogistic"), is even more of a knot to untangle. Mathematically, students have a habit of treating unknown functions as though they're linear (e.g. cancelling the squares in ). I'd be stunned if that metaphor didn't transfer to how we talk about unknown functions in prose.

So who's at fault? Certainly not laypeople for not using absurd words like "monotonically increasing" or "second derivative". Some fault lies with Clear for using a graph without understanding what it implied or what properties he cared about, but these effects are bigger than him. The language of mathematics gives legitimacy because it is so precise, and therefore rhetors naturally devalue it through using it imprecisely. That's just the Circle of Life.

In this case, the imprecision is part of a structure so vast it's boring. The deception took place both on a micro level (exponential as in "convex" or as in "increasing"?) and a macro one (are these numbers a claim, evidence, or a metaphor?). The mathematical myopia causes a metaphorical myopia, and we end up unsure whether the "compounding" Clear refers to is the rapid ballooning of compound interest or the constant accumulation of a junk drawer. Readers either don't notice or take the issue with a grain of salt, for a smorgasbord of reasons. Perhaps they believe Clear's math is representative because numbers are a sort of shorthand for factuality; perhaps they see the issues but find the toy equation genuinely motivating. Whatever the case, the myopia persists, and figuring out what the 37.8 equation properly signifies ceases to be an investigative task, in favor of a hermeneutic one.

Going forward

That's perhaps the most horrifying part: none of these metaphors matter very much.

The book opens by discussing a team of British cyclists who did the sort of compounding "1% habits" that Clear suggests. They go so far as to paint the inside of their team's bus to better find dust that could mess with the equipment9 (14). The book credits their success to these compounding habits, and celebrates their rise from total losers to "the most successful run in cycling history" (15). After this phrase, though, there is a footnote:

As this book was going to print, new information about the British cycling team has come out.

In the footnote he provides a blog post with an elaboration: some of the success of this record-winning team was possibly due to drug use, ranging from merely sketchy to active violation of the World Anti-Doping Agency. At the time of Clear's 2018 blog post, the investigation was ongoing, but as of right now the chief doctor is banned for another couple years for "essentially handing out testosterone like it was nutrition".

This is my absolute nightmare scenario as a writer, and to his credit Clear handled it well. He didn't have to add this footnote at all, much less admit that the story is "more complicated than [he] believed". But he opens with these paragraphs:

...I'm going to provide more detail about the British Cycling team on this page, but before I do, I want to remind you about a key point:

The first chapter of Atomic Habits is not about cycling, but rather about how habits compound over time and why making small improvements on a daily basis can lead to a significant difference in the long-run. It's about the philosophy of continuous improvement and why that's useful. As I describe the details of the British Cycling story below, I don't want you to lose the forest for the trees.

This cycling example is the first thing we see in Chapter 1, the first piece of evidence for the effectiveness of aggregating habits. Throughout the book he references the bikers as an example of a group that found success through his "habit stacking" paradigm. So how can it be that the veracity of this claim isn't important? If a peer-reviewed paper said "We found this result in mice, with huge implications for humans", retracted the mice part, then said "It's all good, this paper isn't about mice anyway", we wouldn't entertain it. So why would we do the equivalent here?

Well, it's simple: For the most part, this biker story tells us what we already know, that good habits give good results. This piece of evidence ratchets up the importance of that belief, makes it seem like the sort of thing you could sell 15 million copies of, sure. But knowing that it's false should at worst reset us to our priors.

This is why I referred to this process as horrifying. Despite their grandiosity, the syllogisms in the book are hollow, weightless. It's filled with fake pillars in places we'd expect them, providing no structural support, but tying the room together.

Similarly, the 37.8 metaphor-equation fails to prove that habit forming is worth it, or describe the effects of habit forming beyond "good". But discounting habit forming for that reason would be the fallacy fallacy. At worst, all I can say is that I'll mistrust the author as I continue to read. The boring truth, that habits are good, remains. I'm still open to some of his more concrete ideas on the mechanics of habit formation, ideas from which Clear may be speaking with more expertise. I expect at least some of them to be effective, a fine way to get habits that have linear-to-diminishing returns. That's not what he promised, but that's fine by me. Cultivating virtue is its own reward. Plus, the boxer who got diminishing returns beats the ever-loving shit out of the boxer who got no returns.

My mom was recommended three self-help-type books as a graduation present for me. She read all three, rejected one of them because it was boring, and bought me the other two. That was kind of peak of her.↩

I don't have a better segue into this, but I really want to share it, so here goes. Speaking of self-help books, I made a YTP of a classic Big Joel video about The Love Languages. Check it out, raise my average watch time, et cetera.↩

If I were a video essayist my mandatory four-hour video would be going through the 77 Winning Strategies for Restaurant Management and getting us all inundated by the banal horror of "self-help for managers". It's bad and bizarre, but not especially bad and bizarre, and because of that you get an inexplicable sinking, dizzy feeling that you could understand the entirety of the universe if you kept reading about how this guy knows a guy who had a bad experience at Wendy's once and now we know that employee dress codes are important. It would not just be my Somerton Files, it would be my Moby Dick, a gesamtkunstwerk that describes a vibrant universe with only one color of paint.↩

He also calls it the "valley of disappointment", after the visual picture of the graph, and I just have to ask what gives. I'm valiantly pro-mixed metaphor, but if anything a plateau and a valley are separate parts of the same allegorical terrain. This threw me off for a while!↩

Here I'm talking exclusively about monotonically increasing functions— functions that keep growing and growing. Obviously other functions exist, but we're not really talking about those functions here because we don't use those functions as metaphors in real life. I'm also taking some liberties with convexity, particularly with regards to the local-global distinction.↩

Strictly speaking, the spread of a pandemic is best described as logistic growth, which roughly means "exponential growth but it peters off when it reaches the population cap".↩

Equivalent isn't the right word in a technical sense, because often times the "equality" isn't transitive. That is, a speaker who understands that "big" doesn't mean "convex" might use "exponential" as a synonym for both in different situations.↩

For example, a "linear thinker" thinks sequentially, straightforwardly, or syllogistically; as far as I can tell this sense of the word has nothing to do with functions of proportional increase. Thus when someone talks about "the myth of linear progress" it's difficult to determine whether there's a relation to , and what is to be made of it if there is.↩

I'm writing this footnote several days after posting because it just occurred to me that I don't consider painting a bus a habit, but whatever I guess.↩